Navasota's First Famous Artist!

by Russ Cushman

Never the less, this beginning set Kathleen's path, which grew into a lifelong passion for art. She ultimately devoted her artistic skill to teaching and capturing intriguing cultures, beginning with her hometown and its people. Kathleen became accomplished in the modern styles of the day, especially regionalism and cubism, and she was a respected art instructor for many years, as she explored drawing, painting and printmaking.

Blackshear graduated from Navasota High School in 1914 and enrolled at Baylor University in Waco, where she earned her Bachelor of Arts degree. Pressing the idea of establishing the Armstrong Browning Library on that campus, she began a lifelong pattern of advancing art and literature. Fittingly, her picture was placed in the cornerstone upon the construction of the Browning Library in 1950.

Blackshear went to New York, and studied at the Art Students League in New York. While there she worked under the famed sculptor, and brother of Gutzon Borglum, Solon Borglum in 1917. Borglum, a former rancher and Paris-trained sculptor, was working on an art text that leaned heavily on an academic approach to art, which may have helped young Kathleen find her own path, that opposite of his. When she reached the age of twenty-one, she travelled in Mexico and then Abroad. She began taking various design jobs and teaching. When Kathleen returned to her formal education, the fall semester of 1924 found her at the Art Institute of Chicago, a melting pot of new ideas. She studied under Charles Fabens Kelley, William Owen, John Norton and Helen Gardner, author of a popular art history textbook used in colleges all over North America.

In her Art Through the Ages, Helen Gardner’s revolutionary multi-cultural approach to art history made a profound impression on generations of American artists, including Blackshear, whose work reflected this perspective for the rest of her life. Blackshear would often incorporate African, Mexican and Asian influences in her work, and her subjects were often from these cultures. By 1926 Kathleen Blackshear was teaching art history at the Institute under the supervision of Helen Gardner, beginning a lifelong friendship as well as a career in art education.

Like her mentor, Blackshear would often take her students to the Oriental Institute or other places where art from non-Western cultures was on display. Gardner and Blackshear encouraged their students to make the leap from looking at these works as anthropological artifacts to studying them as works of Fine Art. This introduction to the world of art made a profound influence on their art students, who began to see art history as the study of art, as well as history.

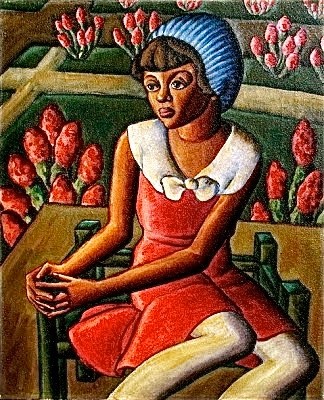

As the American Depression began to unfold, artists were hired through government programs to paint public art in libraries, post offices and courthouses. The search was on for those lasting images and icons of American culture. Rejecting academicism, Kathleen Blackshear focused on the cultures of her own youth and began to paint the life and people of Grimes County Texas, where she grew up. She especially took on a study of the black people she knew and loved, and began to paint them in the monumental, heroic style known as Social Regionalism. Her forms were solid, heavily shaded, with somber expressions; laborers working in a blackened landscape with little sunshine. Her paintings evoked the timeless drudgery of farm life, the hardships of living in rural America, the reduction of men to beasts of burden, and women to mere breeding stock.

Kathleen finished her Master’s degree in 1940. During this time she found inspiration in abstract compositions, fashioning flamboyant geometric rearrangements of animals, African masks, and still-lifes. She also experimented with ceramics, and grew to love batiks, a complex treatment of fabric with dies and wax.

The Witte Museum in San Antonio, Texas hosted her first one woman show in 1941. Blackshear was featured in dozens of group exhibitions, including ones at the Texas State Fair, Art Students League of Chicago, the Chicago Society of Artists, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts of Houston, the Fort Worth Museum of Art (Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth), Dallas Museum of (Fine) Art and at Rice University, in Houston.

Kathleen Blackshear also left a legacy in print. She illustrated at least two books, including Art Has Many Faces: The Nature of Art Presented Visually by Katharine Kuh (1951), wrote two plays, and served as editor for the 1936 and 1948 revisions in Gardner’s Art Through the Ages.

Blackshear retired in 1961, and returned to Navasota, where she lived with her lifelong companion and fellow artist Ethel Spears. Both women had been shaped by the Social Regionalism of the 1930’s as espoused by Grant Wood and others, but Blackshear had developed at least two distinct styles, and had equal prowess as an Abstract artist. Whereas Spears made busy, almost naive genre illustrations of people and factories and whimsical farm-life scenes, Blackshear painted many stylized portraits, often with cubistic treatment of her subjects. Where Blackshear saw the legacy of slavery, and alluded to it through symbolism, Spears saw quaint country lifestyle, in all its simple glory. Each artist’s style represented the philosophical answer to the other. Blackshear and Spears taught private art lessons to Navasota youth for many years.

Kathleen Blackshear is fondly remembered in Navasota as someone who ignored social barriers and befriended Blacks, and as the first woman in Navasota to dare to wear pants in public. She and Ethel Spears scoured the Grimes and Brazos County countryside, painting scenes of the disappearing cotton culture, and edifying the Black field laborers who had been the foundation of the cotton industry for one hundred years.

As her art exhibitions began in San Antonio, so they also ended. In 1968, Kathleen Blackshear made her last exhibit at HemisFair in San Antonio. This same year she received the title, long deserved, of Professor Emeritus from the Art Institute of Chicago.

Kathleen Blackshear died on October 14, 1988, and was buried in Navasota in Oakland Cemetery.

Her work is actively sought by collectors and museums as significant to art done by American women, before and leading to the Civil Rights Movement, and is preserved at several museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Art Institute of Chicago, and Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas.

enough